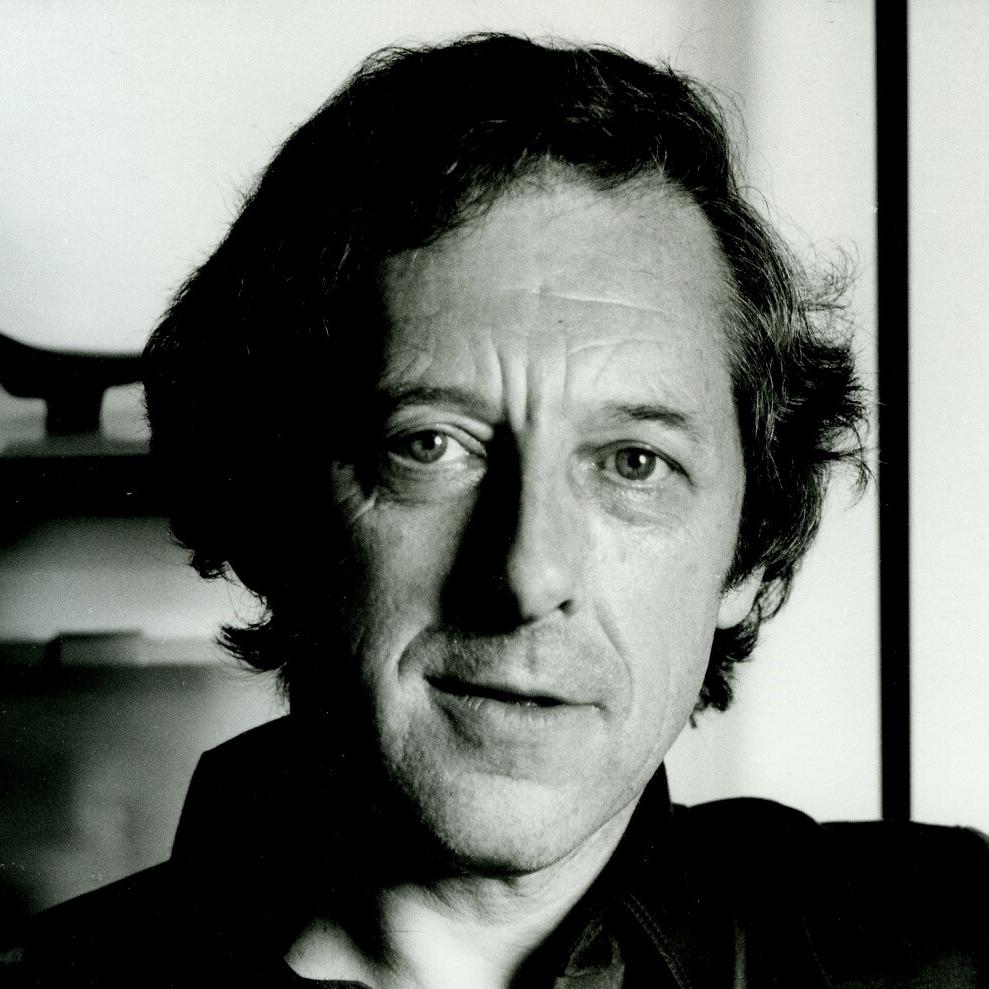

ABOUT MALCOLM

Professor Sir Malcolm Bradbury

Andrew Motion and Kazuo Ishiguro (two of Malcolm’s best known former students) paid tribute in an article in the Guardian 28th November 2000:

“The door of a room adjoining opens a little; a dark, tousled-haired head, with a sad visage, peers through, looks at Howard for a little, and then retreats. The face has a vague familiarity; Howard recalls that this depressed-looking figure is a lecturer in the English department, a man who, 10 years earlier, had produced two tolerably well-known and acceptably reviewed novels, filled, as novels then were, with moral scruple and concern.

“Since then there has been silence, as if, under the pressure of contemporary change, there was no more moral scruple and concern, no new substance to be spun. The man alone persists; he passes nervously through the campus, he teaches, sadly, he avoids strangers.”

In these words, Sir Malcolm Bradbury, who has died aged 68, made his own Hitchcockian, though uncharacteristically reclusive, appearance in The History Man, his greatest and most influential novel. His death marks the close of half a century of academic and literary history, of which he was par excellence the chronicler.

Malcolm Bradbury was born in Sheffield

Malcolm Bradbury was born in Sheffield, the son of Arthur Bradbury, a railway worker, and his wife Doris, and grew up in Nottingham, where he attended West Bridgford grammar school. He took a first-class degree in English at the then fairly new University of Leicester, and did postgraduate work at Queen Mary College, London, at Manchester and in the United States, before taking up his first full-time appointment in 1959, in the adult education department at Hull University.

In 1961, he moved to the English department of Birmingham University, where he met another recently- appointed lecturer, David Lodge, with whom he was to form a long and close friendship and amiable rivalry. In 1965, he joined the new University of East Anglia, and, in 1970, became professor of American studies; he was to remain in Norwich for the rest of his life.

Bradbury was a prolific writer – as an academic critic, as a novelist and humorist, and for television, a medium which increasingly fascinated him. His many critical works included The Modern American Novel (1983), No, Not Bloomsbury and The Modern World: Ten Great Writers (both 1987), From Puritanism To Postmodernism: A History Of American Literature (with Richard Ruland, 1991) and Dangerous Pilgrimages (1995).

He also edited The Penguin Book Of Modern British Short Stories (1987) and The Atlas of Literature (1996), to which he was also a major contributor over an astonishingly wide range of topics. His original television dramas included the two four-part series, The Gravy Train (1990) and The Gravy Train Goes East (1991), both sharp and uncomfortably accurate satires on the politics of the European Community, as well as Cuts (1996), which contrasted the visible consumption of television companies with the starvation of universities in an age of sado-monetarism.

Apart from his original scripts, he adapted a wide range of books for television, ranging from Tom Sharpe’s Porterhouse Blue and Kingsley Amis’s The Green Man to Stella Gibbons’s Cold Comfort Farm and the Dalziel and Pascoe novels of Reginald Hill. It is a matter of regret that his adaptation of William Cooper’s Tales From Provincial Life, a novel with which he had particularly close affinities, has not yet reached the television screen.

“Like most comic novelists, I take the novel extremely seriously”

Bradbury, however, made no secret of the fact that fiction, and in particular the novel, was his true love. “Like most comic novelists, I take the novel extremely seriously,” he said. “It is the best of all forms – open and personal, intelligent and inquiring. I value it for its scepticism, its irony and its play.” His first novel, Eating People Is Wrong, which picked up the baton from Kingsley Amis’s Lucky Jim, appeared in 1959 and was an instant success – though it owed more to American writers like Trilling and Bellow than to Amis.

From then on, his novels appeared at the rate of roughly one a decade, with Stepping Westward (1965), The History Man (1975), Rates Of Exchange (1982), Dr Criminale (1992) and To the Hermitage (2000), based on Diderot’s visit to the court of Catherine the Great, a brilliant departure from the form which he had made so much his own.

In almost all of Bradbury’s novels, the most frequently recurring theme is that of the slightly naive, liberal innocent, usually an academic, hilariously abroad in an unfamiliar, and occasionally slightly threatening, context, a theme which developed naturally from his frequent foreign travels, often under the auspices of the British Council. In Rates Of Exchange, the imaginary Slakan language was largely invented over several years by the combined contributions of the polyglot participants of the council’s annual Cambridge seminar of contemporary writing, of which Bradbury was the founder and, for many years, chairman.

Of all his novels, however, it was The History Man by which he will be most lastingly remembered, and which indeed was one of the outstanding novels of its decade. It charts the successful career of the manipulative and promiscuous radical sociologist, Howard Kirk, at the new University of Watermouth (which bears more than a passing resemblance to East Anglia), and satirises savagely his substitution of “trends for morals and commitments”.

Kirk moves through the university like a Marxist Iago, wrecking careers, corrupting innocence and generally subverting stability in the name of history. “I know how your aggression operates,” one of his more perceptive colleagues tells him. “If you wanted someone through a window, you wouldn’t push him yourself. You’d get someone else to do it. Or persuade the man he should do it himself, in his own best interests.”

All Bradbury’s novels, for all their surface wit and comedy, have serious moral and philosophical subtexts; in The History Man the wit is darker, the satire more biting, the atmosphere more menacing and the conclusion more hopeless. Bradbury was always fascinated by the experimental fictive techniques of contemporary American novelists, and The History Man shows a marked development in his own writing in its unvaried use of a present tense, which reports without comment or analysis the speech and actions of the characters. The technique adds menace to the atmosphere of alienation and moral nihilism.

Bradbury’s contribution to the literary life of his time was as extraordinary as his prolific output, and deserves equal notice. He will be properly remembered for his part, with Angus Wilson, in founding in 1970 – and, for many years, teaching – the creative writing programme at East Anglia. At the time the only MA of standing in the subject in Britain, and today, in spite of many imitators, still the most distinguished – not least in the number of distinguished writers it can claim as graduates – it did much to allay the suspicions of such courses.

His generosity to all literary ventures he regarded as worthy was remarkable, and his inability to reject appeals for help was a severe trial to his agent. The list of organisations to which he was prepared to give precious time was impressive, and included the Booker Prize management committee, the British Association for American Studies, the SDP arts policy committee, the Eastern Arts Association, the King’s Lynn literary festival and the Norwich festival.

To few, however, did Bradbury give as much time and attention as he did to the affairs of the British Council, of whose literary work, at one time very much under threat of abolition, he was an invaluable supporter. Apart from serving as a foundation member of its literary advisory committee, he was single-handedly responsible for transforming its contemporary writing seminar, the chairmanship of which he took over in 1976, from a rather routine English studies event into one which brought together writers, translators, journalists, publishers and academics from all over the world to meet British writers, many of whom found foreign translators and publishers at it.

The seminar took place during an annual fortnight in a Cambridge college, and was conducted, in sympathy with his own love of parties, in appropriately carnival conditions. After relinquishing the chairmanship to Christopher Bigsby in 1984, Bradbury continued to revisit the seminar every year to give readings, his visits invariably providing an occasion for a party of Bradburyesque proportions.

His tours overseas for the council, many of which reappeared transmogrified in his novels, were invariably marked by unscheduled revelry, as well as by serious literary discussions. After retirement in 1995, he found a new platform, and a new source of conviviality, as a guest lecturer on Swan Hellenic cruises.

When the British Council’s literature department decided to produce an annual anthology of the most recent British writing it could use to publicise new young writers abroad, it was natural for it to look first to Malcolm Bradbury for help and encouragement, and as an editor of the first two volumes (1992 and 1993). This was a time when the publication of an anthology launched under the council’s auspices was hardly calculated to produce favour- able reviews, however illustrious the editor.

It was largely due to his support that New Writing (named, at his suggestion, in honour of John Lehmann’s earlier venture) survived a difficult birth, and went on to become one of the few refuges for the short story in the 1990s. Many of his own creative writing graduates first published in the series.

If he was pre-eminently a gregarious man, happiest in the social context of conferences, seminars and meetings, and generous with his friendship, Bradbury was even more markedly a devoted family man. In 1959, he married Elizabeth Salt, who was, throughout his life, the greatest single source of happiness and support to him, and by whom he had two sons. He was appointed CBE in 1991, for services to literature, and was knighted in 2000.

Literary London is much the poorer for the loss of its own History Man, and of a voice unequalled for its humanity and wit.

Malcolm Stanley Bradbury, writer and teacher, born September 7 1932; died November 27 2000.